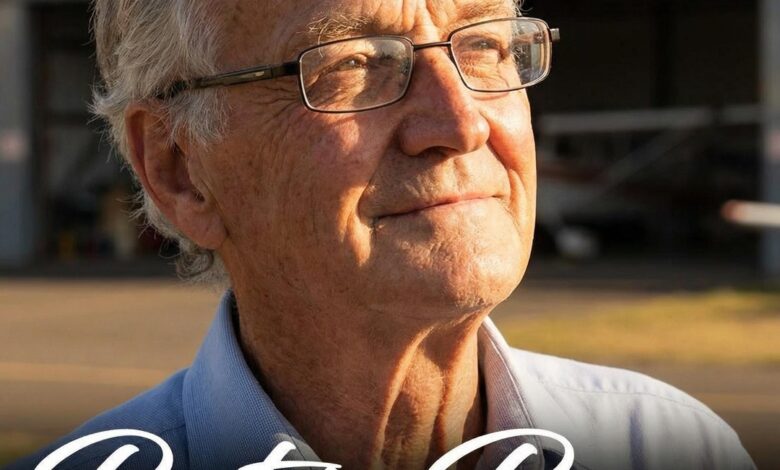

Remembering a Remarkable Individual Whose Legacy Will Be Cherished!

The global conservation community stands in somber reflection following the passing of a titan in the field of wildlife biology—a man whose profound dedication redefined the human understanding of the African elephant. For over six decades, he lived a life intertwined with the giants of the savanna, peeling back the layers of their complex emotional lives, sophisticated social structures, and hauntingly beautiful communication systems. His work was not merely an academic exercise; it was a crusade of empathy that transformed the African elephant from a mere silhouette on the horizon into a sentient, familial being in the eyes of the world. As tributes cascade in from heads of state, rigorous scientific institutions, and grassroots advocates, the message remains singular: the world has lost its most eloquent voice for the voiceless.

Iain Douglas-Hamilton’s odyssey began in the vast, untamed landscapes of East Africa, where he introduced a methodology that would revolutionize the study of megafauna. Before his arrival, elephants were often studied as a collective mass—a population to be managed rather than a society to be understood. Douglas-Hamilton pioneered the “individual-based” approach, meticulously documenting the unique notches in an ear, the specific curve of a tusk, and the idiosyncratic temperaments that distinguished one elephant from another. By naming these individuals and following them through droughts, births, and the arrival of calves, he constructed the first comprehensive “biographies” of elephants. This shifted the scientific paradigm, revealing the profound depth of matriarchal leadership and the agonizing grief elephants display when a member of their herd falls.

His observations provided the empirical backbone for one of the most significant conservation victories in history. In an era when the ivory trade was decimating populations across the continent, Douglas-Hamilton transitioned from a quiet researcher to a fierce international advocate. Armed with data that proved the systematic collapse of elephant societies due to poaching, he took his findings to the world stage. His testimony and tireless lobbying were instrumental in the historic 1989 global ban on the ivory trade. He understood that to save the species, one had to change the economic and political incentives that drove their slaughter, and he navigated the halls of power with the same steady resolve he used to track herds in the bush.

As technology evolved, so too did his methods for safeguarding the herds he loved. Recognizing that the greatest threat to elephants in the 21st century was the loss of habitat and the fragmentation of their ancient migratory paths, he founded Save the Elephants, a globally respected conservation organization. He pioneered the use of satellite-linked GPS collars, a technological leap that allowed researchers to visualize elephant movements across thousands of miles in real-time. This “eye in the sky” approach revealed the secret maps of the savanna—showing how elephants avoid human conflict zones and trek across international borders in search of sustenance. This data has become the blueprint for modern land-use planning, helping governments establish wildlife corridors that allow for the peaceful coexistence of humans and elephants.

His philosophy of conservation was never elitist or exclusionary. He believed that the survival of the African elephant was inextricably linked to the prosperity of the local communities that shared their land. He championed “respectful stewardship,” arguing that education and empathy were more powerful deterrents to poaching than any fence or firearm. To Douglas-Hamilton, every person living near a wildlife reserve was a potential guardian, and he spent as much time in village meetings as he did in the field. He possessed a rare ability to translate high-level science into a universal language of moral responsibility, inspiring generations of young conservationists to pick up the mantle of his work.

Statistically, the impact of his work is staggering. When Douglas-Hamilton began his research in Lake Manyara in the 1960s, little was known about the territorial requirements of a healthy herd. Today, thanks to the tracking programs he established, we know that an elephant population might require an area of over $10,000\text{ km}^2$ to thrive. His research into “acoustic communication” also opened a new frontier in biology, suggesting that elephants use infrasonic calls—sounds below the frequency of human hearing—to communicate across distances of up to $10\text{ km}$. These scientific milestones provided the world with a sense of wonder that catalyzed funding and political support for conservation efforts.

Despite his legendary status and the numerous accolades he received, including the Order of the British Empire (OBE), he remained a man of humble habit and deep familial roots. He is survived by his wife, Oria—his lifelong partner in both love and labor—and their daughters, Saba and Dudu, both of whom have carried forward his legacy in film and conservation. His six grandchildren grew up listening to stories of the Great Tuskers, inheriting a worldview that prizes the natural world over material gain. Yet, as his family mourns, they acknowledge that his true kin are the thousands of elephants that still walk the earth today because of his intervention.

The legacy of Iain Douglas-Hamilton is not confined to textbooks or the headquarters of his foundation. It is found in the rhythmic thud of a matriarch’s stride across the Samburu plains; it is felt in the silence of a protected forest; and it is reflected in the eyes of every child who learns that an elephant is a creature of memory, love, and wisdom. He proved that a single individual, armed with a pair of binoculars and a heart full of courage, could stand in the path of extinction and turn the tide. As the sun sets on his remarkable life, the echoes of his work continue to reverberate across the continent he called home, a testament to a man who didn’t just study nature—he protected the soul of the planet.

The ivory ban of 1989 remains the gold standard for international wildlife policy, and the GPS tracking systems he developed continue to be the primary tools used by park rangers today to combat sophisticated poaching syndicates. His life was a masterclass in the power of persistence, a reminder that while the challenges facing our environment are vast, the human spirit is equally formidable.