My Classmates Mocked Me for Being a Garbage Collectors Son – on Graduation Day, I Said Something They Will Never Forget!

My name is Liam, and for most of my life, people decided who I was before I ever opened my mouth.

I was “the garbage collector’s son.”

That label came with a smell people swore they noticed, jokes they thought were harmless, and looks that made it clear I didn’t belong. My world carried the scent of diesel fuel, bleach, and old food sealed in plastic bags long before I understood shame.

My mother never planned this life.

She wanted to be a nurse. She was in nursing school, married, living in a small apartment with my dad, who worked construction. They talked about shifts, exams, promotions, a future that made sense. Then one morning, a harness failed on a job site. My father fell. He died before the ambulance arrived.

In a single day, my mother became a widow with debt, no degree, and a child to raise.

The hospital bills came fast. Then the funeral costs. Then the tuition she could no longer afford. Dreams don’t survive long when rent is due and food needs to be on the table. She didn’t get a choice. She put on a reflective vest, climbed onto the back of a sanitation truck, and took the only job that didn’t ask for explanations or credentials.

The city didn’t care who you used to be.

They cared if you showed up before sunrise and kept showing up.

That decision kept us alive. It also made me a target.

In elementary school, kids wrinkled their noses when I sat down.

“You smell like the garbage truck,” they’d say.

By middle school, it was routine. People pinched their noses dramatically when I walked past. Chairs slid away from me in group work. Fake gagging sounds followed me down hallways. I learned where to sit alone, where to eat quickly, where to disappear.

Behind the vending machines near the old auditorium became my safe place. Quiet. Forgotten. Invisible.

At home, I lied.

Every afternoon, my mom came in exhausted, peeling off rubber gloves, her hands red and swollen.

“How was school, mi amor?” she asked, smiling like she hadn’t just hauled other people’s waste for ten hours.

“It was good,” I said. “I sat with friends. Teacher says I’m doing great.”

She lit up every time.

“Of course you are. You’re the smartest boy in the world.”

I couldn’t tell her the truth. She already carried too much: my father’s death, debt, double shifts, and the weight of a life that veered off course. I refused to add my loneliness to that pile.

So I made a promise. If she was going to break her body for me, I would make it worth it.

Education became my escape.

We didn’t have money for tutors or prep programs. What I had was a library card, a battered laptop she bought with money from recycled cans, and stubbornness that bordered on obsession. I stayed in the library until closing. I taught myself algebra, physics, anything that made sense in a world that otherwise didn’t.

At night, my mom sorted bags of cans on the kitchen floor. I did homework at the table. Sometimes she looked up at my notebook.

“You understand all that?”

“Mostly,” I said.

“You’re going to go further than me.”

High school didn’t stop the cruelty. It just got quieter and sharper. No one yelled insults anymore. They whispered. They sent each other photos of the sanitation truck outside and laughed while glancing at me. Teachers noticed my grades but not the cost.

I could’ve told someone. I didn’t. If the school called home, my mom would know. And I wasn’t ready for that.

Then Mr. Anderson noticed me.

He was my 11th-grade math teacher—messy hair, loose tie, coffee always in hand. One day, he stopped at my desk and noticed I was solving problems from a college website.

“Those aren’t from the book,” he said.

I panicked. “I just… like this stuff.”

He sat beside me like we were equals.

“Ever thought about engineering? Computer science?”

I laughed. “We can’t afford application fees.”

“Fee waivers exist,” he said. “So does financial aid. Smart poor kids exist too. You’re one of them.”

From that day on, he became my quiet ally. He gave me extra problems. Let me eat lunch in his classroom. Talked about algorithms like they were gossip. Showed me schools I’d only seen on TV.

“Your zip code isn’t a prison,” he told me.

By senior year, I had the highest GPA in the class. People called me “the smart kid” now. Some with respect. Some like it was an illness.

Meanwhile, my mom pulled double routes to pay off the last of the hospital bills.

One afternoon, Mr. Anderson dropped a brochure on my desk. One of the top engineering schools in the country.

“They have full rides for students like you,” he said.

I didn’t believe him. But we applied anyway. In secret.

The essay nearly broke me. My first draft was safe and empty. He handed it back.

“This could be anyone. Where are you?”

So I started over. I wrote about 4 a.m. alarms. Orange vests. My father’s empty boots. My mother studying drug dosages once and hauling medical waste now. About lying when she asked if I had friends.

When he finished reading, Mr. Anderson just nodded.

“Send that one.”

The email came on a Tuesday morning.

Full ride. Housing. Grants. Work-study.

I waited until my mom came out of the shower before showing her. She read it slowly, hands shaking.

“I told your father,” she cried. “I told him you’d do this.”

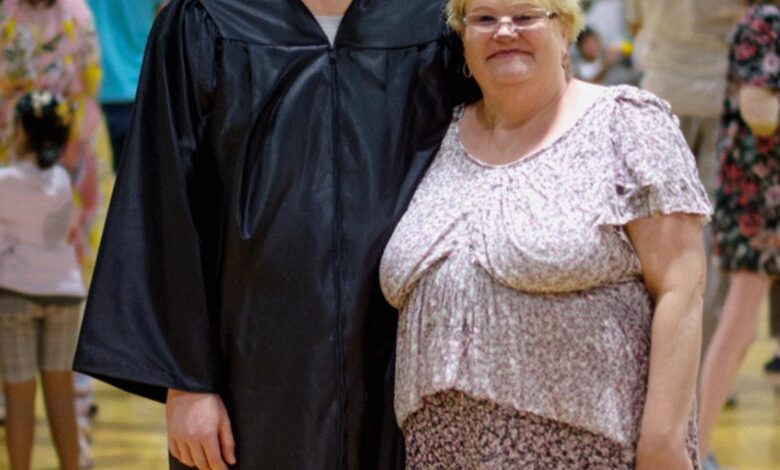

Graduation day arrived heavy with nerves and perfume and noise. The gym was packed. I saw my mom in the back row, sitting straighter than I’d ever seen her.

When my name was called as valedictorian, the applause was polite. Curious.

I walked to the mic.

“My mom has been picking up your trash for years,” I said.

The room went dead silent.

I told them the truth. About the jokes. The shame. The lies I told to protect her. About a woman who gave up her dream so I could have one.

Then I pulled the acceptance letter from my gown.

“In the fall,” I said, “I’m going to one of the top engineering schools in the country. On a full scholarship.”

The gym exploded.

My mom stood screaming through tears. “My son!”

I ended with one sentence.

“Your parents’ jobs don’t define your worth—and they don’t define theirs.”

When I walked off that stage, people were standing. Some crying. Some ashamed.

That night, back home, her uniform still hung by the door. It smelled like bleach and diesel.

For the first time, it didn’t make me feel small.

It made me feel like I was standing on someone’s shoulders.