From sickly to stunning! The polio survivor who became a Hollywood icon! See now!

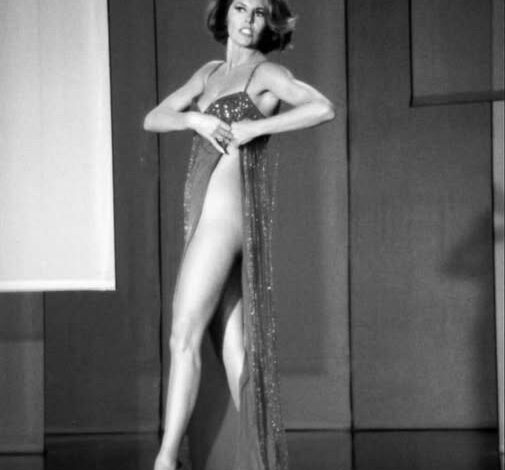

In the golden era of MGM, where the studio system manufactured gods and goddesses with industrial precision, Cyd Charisse occupied a unique pedestal. She was a woman who could seemingly do it all—sing, act, and navigate the complex geometry of a musical number as if the score were a physical force running through her veins. Her silhouette, defined by legendary, endless lines and a poised athleticism, became a Hollywood myth. Yet, the genesis of this screen icon was not found in the dazzle of a soundstage, but in a dusty corner of Texas, born out of a struggle for basic physical survival.

The woman the world would come to know as Cyd was born Tula Ellice Finklea in Amarillo, Texas, in 1922. Her early childhood was defined not by grace, but by fragility. Before she reached her sixth birthday, Tula contracted polio, a terrifying diagnosis in an era before vaccines. The disease threatened to wither her limbs and tether her to a life of physical limitation. In a move that was both practical and prophetic, doctors prescribed ballet lessons as a form of physical therapy—a means to rebuild the strength she had lost to the virus. No one in that small Texas town could have guessed that these careful, remedial exercises would eventually sculpt one of the most magnetic presences in the history of cinema. Her professional name, “Cyd,” was a relic of her childhood, born from her brother’s lisping attempt to say “Sis.” It became the moniker for a transformation from a frail Texas girl into a goddess of the silver screen.

Amarillo in the 1920s was a landscape of big skies and grit, a place where the horizon felt infinite but the opportunities for glamour were scarce. For young Tula, the dance studio offered what the high plains could not: a sense of discipline, a feeling of grace, and a literal avenue for escape. Ballet did more than just repair her body; it re-sculpted her confidence. She learned to turn her physical weakness into a source of immense, controlled power. By her teens, she had outgrown Texas and moved to Los Angeles, where she studied under the rigorous eyes of Russian masters. During her early years on stage, she often performed under Russian-sounding pseudonyms to satisfy the era’s demand for exoticism, but the talent was undeniably her own—poised, athletic, and refined. She successfully married the rigid, classical lines of traditional ballet with a grounded, earthy sensuality that would become her cinematic signature.

Hollywood eventually discovered her through the sheer eloquence of her movement. Charisse didn’t need a monologue to capture a director’s eye; the phrasing of her body was a language unto itself. She signed with MGM in the 1940s, initially working her way up from the bottom of the call sheet. She moved from the ensemble to featured roles, and by the early 1950s, she had become one of the studio’s most luminous attractions. Her breakthrough came in the “Broadway Melody” sequence of Singin’ in the Rain (1952). Draped in a slinky green dress that seemed to shimmer with a life of its own, she radiated a mix of danger and absolute control. She didn’t speak a single line in the sequence, yet she said everything through a tilt of her chin or the predatory whip of a leg. In that one performance, the contract dancer was elevated to an icon.

Uniquely, Charisse holds the distinction of being a preferred partner for both Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire—the two titans of screen dance. She was the rare performer who could match their vastly different styles without being overshadowed. With Kelly, she met his muscular, exuberant athleticism with a cool, sharp precision. With Astaire, she was rhythm personified, appearing lyrical and romantic. Their “Dancing in the Dark” sequence in The Band Wagon (1953) remains a pinnacle of cinematic romance. There is no prologue and no chatter; just two people moving through a park, pulled together by a kind of rhythmic gravity. It wasn’t just choreography; it was chemistry made visible.

The genius of Cyd Charisse was never merely about her physical beauty, though the cameras clearly adored her. It was her timing—the sophisticated way she could stretch and release a beat. Her ballet training gave her incredible line and control, but she possessed the jazz-like intuition to know when to bend the rules. She could melt classical shapes into something more modern and provocative, shifting from a hushed stillness to a blaze of movement in a heartbeat. While other dancers sought to dazzle with pure speed, she hypnotized her audience with restraint, making them feel the breath before a turn and the tension of a half-second of hesitation.

Throughout the 1950s, she became the shorthand for elegance. She brought mystery to Singin’ in the Rain, sophistication to The Band Wagon, a luminous, ethereal grace to Brigadoon (1954), and a dry, sharp wit to Silk Stockings (1957). In Party Girl (1958), she proved she could handle darker, more dramatic material, playing a nightclub dancer caught in the gears of the underworld. She demonstrated that she could carry a scene with the same gravitas she used to carry a dance number.

Offscreen, however, Charisse bore little resemblance to the femme fatales she portrayed. She was a woman of quiet, steady calm and rigorous professionalism. In an industry fueled by scandal and excess, she remained a pillar of stability, maintaining a devoted sixty-year marriage to singer Tony Martin. They were a rare Hollywood success story, raising two sons and living by a simple mantra: “We never tried to outshine each other.”

Despite the outward glamour, pain still marked the contours of her life. In 1979, tragedy struck when her daughter-in-law was killed in the crash of American Airlines Flight 191, one of the deadliest disasters in aviation history. Those who knew her said she was shattered by the loss, yet she navigated her grief with the same composed strength that defined her dancing. She stepped back from the spotlight to focus on her family, eventually returning to teach younger generations. Dancers sought her out not just for her technique, but for the discipline and humility she embodied.

Recognition for her contributions arrived with fitting prestige. In 2006, President George W. Bush awarded her the National Medal of Arts. It was a moment of profound closure: the little girl who had to relearn how to walk through ballet was now being honored as one of the greatest artists in American history. When she passed away in 2008 at the age of eighty-six, she left behind a body of work that remains incandescent.

Cyd Charisse showed the world that beauty needn’t be fragile and that true elegance is a product of fierce discipline and profound resilience. Her life was more than a Hollywood success story; it was a study in how to turn physical vulnerability into a source of enduring power. She didn’t just survive polio; she conquered it, and in doing so, she gave the world a language of movement that still sings across the decades. Even now, when the lights dim and her image appears on screen, you can feel the quiet miracle of a woman who turned recovery into a high art.