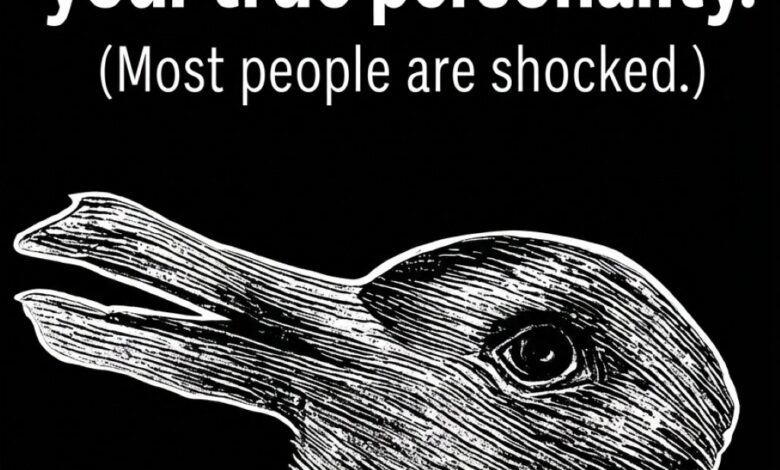

What the First Animal You Notice May Say About Your Personality!

The human mind is a sophisticated processing engine, an intricate web of synapses that constantly filters an overwhelming torrent of data into a coherent reality. We often take for granted that our perception of the world is an objective truth, yet we are frequently confronted with the startling reality that two people can stare at the exact same scene and walk away with fundamentally different interpretations. This phenomenon highlights the subjective nature of the human experience, revealing that what we “see” is rarely a mirror image of the world, but rather a construction shaped by our habits, instincts, and the unique architecture of our cognitive styles.

Optical illusions serve as a fascinating gateway into this internal landscape. They sit at the delicate intersection of neurology and psychology, acting as a visual stress test for the brain. When we encounter an ambiguous image, our brain hates the vacuum of uncertainty; it seeks to impose order and meaning almost instantaneously. Before our conscious, reasoning mind has a chance to intervene, our intuition and subconscious preferences make a split-second executive decision about what the image represents. This initial commitment—the “first impression” of the mind’s eye—is often a reflection of how we are wired to process information.

One of the most enduring tools in the study of perception is the “dual-image” illusion, a drawing that contains two distinct animals cleverly integrated into the same set of lines and shadows. The beauty of these images lies in their perfect equilibrium; neither interpretation is more valid than the other, and the lines themselves never change. What changes is the viewer’s internal focus. This visual choice acts as a playful Rorschach test, offering a window into whether a person’s mental defaults lean toward the structured and analytical or the fluid and imaginative.

For those who immediately identify one specific animal—often the one defined by more rigid lines or a clear, identifiable silhouette—it frequently suggests a mind that thrives on logic, structure, and empirical detail. This cognitive style is deeply rooted in the left hemisphere’s traditional strengths: linear thinking, sequencing, and the deconstruction of complex problems into manageable, bite-sized pieces. If you are someone who spots the structural animal first, you likely move through the world with a practical lens. You value clarity over ambiguity and efficiency over idle speculation. In a professional or social setting, you are the person who seeks the most direct path from point A to point B, relying on facts and tangible evidence to guide your decision-making. Your greatness lies in your ability to organize the chaos of the world into a coherent, actionable plan.

Conversely, those whose eyes immediately gravitate toward the second animal—perhaps the one hidden in the negative space or suggested by softer, more abstract curves—often possess a mindset characterized by creativity, synthesis, and intuition. This perspective is less concerned with the individual parts and more focused on the “gestalt,” the whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. If this was your experience, your brain may naturally lean toward the symbolic and the possible. You are likely comfortable with nuance and the gray areas of life, enjoying the process of exploring an idea for its own sake rather than just for its utility. You see connections where others see silos, and your intuition acts as a sophisticated internal compass that often finds the right answer before you can even explain how you got there.

However, the true marvel of human perception is not that we fall into one of these two camps, but that our brains are capable of “bistable perception”—the ability to eventually switch between the two views. While we all have an initial preference, the moment the second animal “clicks” into view is a moment of cognitive expansion. It represents the brain’s incredible plasticity and its capacity to reframe reality based on a simple shift in attention. This flexibility is perhaps our most valuable intellectual asset. It allows the scientist to dream of a new theory and the artist to master the technical precision of their craft.

Beyond the playful personality insights, these illusions remind us of a profound social truth: the world is rarely what it seems at first glance, and our “truth” is rarely the only one available. When we realize that our own brains can be “tricked” by a few clever lines on a page, it humbles our certainty. It suggests that when we disagree with others—whether about a piece of art, a political stance, or a personal conflict—the disagreement might not be rooted in a lack of intelligence, but in a fundamental difference in how our internal filters are organized.

In the digital age, where we are bombarded with information designed to trigger our immediate, instinctive reactions, understanding the mechanics of perception is more important than ever. We are living in an era of “cognitive niches,” where our social media feeds and news sources cater to our existing biases, reinforcing the first animal we see and hiding the second. Practicing the mental effort required to see the “other” animal in an illusion is a small but potent exercise in empathy and intellectual humility. It trains the mind to look past the obvious and to seek out the hidden layers of reality that reside in the negative space.

Ultimately, whether you see the eagle or the lion, the rabbit or the duck, the value lies in the act of looking. These visual puzzles are less about labeling who we are and more about celebrating the diverse ways in which we inhabit our own minds. They remind us that the human brain is not a passive receiver of light, but a creative storyteller, weaving a unique narrative for every pair of eyes that opens to the world. By appreciating the “other” animal, we don’t just see a different drawing; we begin to see a different world.